The FDIC Meeting That Blew Up the Internet

B-School Search

For the latest academic year, we have 185 schools in our BSchools.org database and those that advertise with us are labeled “sponsor”. When you click on a sponsoring school or program, or fill out a form to request information from a sponsoring school, we may earn a commission. View our advertising disclosure for more details.

Most of us know the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or FDIC. That’s the U.S. government agency that provides deposit insurance for customers in the unlikely event their bank fails.

In November 2022, the FDIC’s Systemic Resolution Advisory Committee (SRAC) met in Washington to discuss the “resolution of systemically important financial institutions.” The FDIC had asked the committee for recommendations on what policy and tactical actions to take if an American tier-one bank—a large, well-capitalized financial institution essential to the banking system—was in danger of collapsing. Examples of tier-one banks include Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo.

But when excerpts from the meeting’s video hit social media, the outrage wasn’t far behind. This report takes a look at why the SRAC meeting suddenly fueled so much intense scrutiny and controversy.

What is a Bank Bail-In?

Much of what the committee discussed during that meeting concerned a controversial and relatively new resolution technique known as a “bail-in” that’s unfamiliar to most of us, including many knowledgeable MBA students and alumni.

Bail-ins were first proposed in 2010 in response to the 2008 global financial crisis and the subsequent Great Recession. During that period, hundreds of United States banks failed, and the government injected $700 billion worth of taxpayer funds into major banks like Bank of America and Citigroup to bail them out. Also receiving tax money were closely related organizations critical to the financial infrastructure, such as the insurance provider American International Group, also known as AIG.

Driving the development of bail-ins as an alternate solution was the widespread public outcry over the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) that rescued financial providers like these that were “too big to fail” because the stability of the entire banking system depended on their functioning.

In short, a bail-in provides a mechanism where a struggling financial institution’s own creditors rescue that firm. Unlike a traditional bank bailout, which is typically funded by taxpayers, a bail-in provides a method for a bank to recapitalize itself without any outside funding assistance.

A bail-in amounts to the opposite of a bailout because the former will not rely on external parties like governments and taxpayers to infuse capital. Both of these mechanisms are designed to preclude a failing bank’s complete collapse, but they’re different in terms of who specifically bears the financial burden that the bank’s rescue will require.

In a bail-in, a bank would restructure its capital by converting debt into equity to stay afloat. That means the bank would use funds from unsecured creditors to satisfy its need for more capital. Unsecured creditors include the bank’s borrowers like bondholders, but they also include other groups, and hence this is one aspect that’s invited considerable scrutiny in the wake of the SRAC’s meeting.

What most people don’t realize is that under a bail-in operation, funds belonging to depositors can indeed be used to help recapitalize the bank. It may be true that the risk of losing deposits is only borne by wealthy large account holders with more than $250,000 on deposit since the FDIC insures all deposit accounts up to $250,000.

But astonished observers who watched the video of the meeting heard the members cavalierly toss around statements about how these days bank debt is “not principle-protected by design.” And all these viewers started to wonder how banks ever acquired the ability to recapitalize themselves using depositors’ funds in the first place.

Statutory Authorization for Bail-Ins

In response to the public outrage after TARP rescued the banks that were too big to fail, bail-ins became an available legal option through the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Known today as Dodd-Frank, this legislation overhauled the regulation of almost every sector within the financial services industry in the United States, and its sweeping changes affected all federal financial regulatory agencies. One of the measure’s most significant provisions is the use of taxpayer funding to rescue any failing financial institution as a last-resort solution.

The Dodd-Frank bail-in provision was actually an adaptation of a multinational framework designed a few months before by the European Union in response to the financial crisis in that region. That framework is known today as the Basel III International Reforms, and like the other Basel Accords since 1978, it is administered by the Bank of International Settlements.

During deliberations before the votes on these measures, European and American policymakers supporting the bail-in procedure relied on several justifications. They argued that enabling banks to transform their debt into equity would release the pressure on taxpayers to cough up money under the threat of a systemic collapse of the banking system.

They also contended that the bail-in procedure was essential to provide relief in the event of banking collapses inside financially strapped, distressed jurisdictions where tax revenues weren’t available, such as Greece, Bulgaria, and Croatia. The proponents also argued that forcing banks to apply an internally executed bail-in strategy was the only practical means to force banks to exercise more corporate responsibility on behalf of their stakeholders, including their investors, borrowers, and depositors.

It’s also important to note that one of Dodd-Frank’s key provisions was included to prevent a systemic disaster across the financial industry. The legislation stipulates that securitized financial contracts like derivatives must be preferred over the claims of unsecured creditors such as borrowers and depositors. That’s because derivatives are investments that banks often trade among each other, ostensibly to hedge their investment portfolios against downside risk. Currently, the top 25 banks hold over $206.1 trillion in derivatives—a substantial risk to the financial system if those investments ever became unprotected.

However, despite some of the hyperbolic misinformation circulated on social media in response to the SRAC’s meeting video, banks in financial trouble cannot arbitrarily or capriciously confiscate the money belonging to their depositors. Under Dodd-Frank, regulators at either the FDIC, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Reserve System, or a state’s financial protection department would first need to exercise their statutory authority to place a bank holding company into receivership and under federal control. Only then would the regulators implement a plan to convert its debt into equity.

Emerging Related Controversies

Once observers latched on to the video of the SRAC meeting, additional controversies related to the committee’s discussion about bail-in procedures quickly started emerging.

Insufficient FDIC Capitalization

One such controversy involves the FDIC’s capitalization. Because under normal circumstances, at most only three or four United States banks might fail in a given year, the FDIC has more than enough funding to reimburse their depositors.

But what might happen if—as a consequence of a fast-spreading financial panic only possible since the dawn of the internet age—a widespread bank run were to target financial institutions nationwide simultaneously with withdrawal demands?

Currently, banks hold about $17 trillion in deposits within the United States banking system. However, the FDIC only holds about $124.5 billion in capital, or only about 0.56 percent of the aggregate deposits. The FDIC can rely upon an additional $100 billion line of credit from the Treasury Department, which would help insure about 1.26 percent of the deposits. In normal times, that total would be more than adequate to manage the few banks that fail each year.

But the fact remains that the FDIC is unprepared for a widespread, large-scale bank run across the nation. It is so vastly undercapitalized that in such a catastrophic event, only a tiny percentage of the depositors could ever receive reimbursement.

No More Reserve Requirements

A second controversy involves changes to fractional reserve requirements. For most of the Federal Reserve’s history, the system had a regulation in place mandating that banks had to set aside and store at least 10 percent of depositors’ funds at all times. Banks were prohibited from loaning out that 10 percent, and they also couldn’t use that percentage for trading within the financial markets or funding operating expenses. The Fed required that banks keep that percentage ready and immediately available to defend against the unlikely but very real possibility of a bank run by customers who wanted to withdraw their funds simultaneously.

But believe it or not, in March 2020, while most customers were distracted by the Covid crisis, the Fed quietly eliminated the reserve requirement. In other words, today’s banks aren’t required to keep any percentage of deposits immediately available for customer withdrawals. In fact, these days they’re not even required to keep as little as 1 percent on hand.

In other words, the banks must wait to make local reserve cash immediately available to depositors, as they could before 2020, because these institutions instead are now free to loan out those funds or earn returns by investing them. This new policy isn’t exactly one that engenders a lot of confidence among customers who worry about immediate access to their funds.

A Code of Silence at the FDIC?

If what we’ve just reported about bail-ins, an undercapitalized FDIC, and the canceled reserve requirement isn’t disconcerting enough, now we come to a disturbing remark by one of the more outspoken, high-profile committee members.

The quote that follows is from Gary D. Cohn, the former director of the National Economic Council and chief economic advisor in the Trump White House from 2017 to 2018. He’s currently the board’s vice chairman at IBM after working at Goldman Sachs for 25 years, most recently as president, and has delivered presentations to many of the World Economic Forum’s meetings in Davos since 2010.

Cohn told the committee:

I almost think you’d scare the public if you put this out. Like, why are they telling me this? Should I be concerned about my bank? Like, my insurance company doesn’t tell me what they’re doing with my assets—they just assume they’re going to pay my claim, right?

I think you’ve got to think of the unintended consequences of taking a public that has more full faith and confidence in the banking system than maybe people in this room do. (laughter)

We want them to have full faith and confidence in the banking system. They know the FDIC insurance is there. They know it works. They put their money in. They’re going to get their money out. So there’s a select crowd of people that are on the institutional side. And if they won’t understand this, they’re going to find a way to understand this. There’s a bunch of law firms represented in this room. There’s a bunch of people that’ll change them by the hour and a lot of money to explain this all to them. And I don’t have a problem with that, and they all have huge staff.

But I would be careful about the unintended consequences of starting to blast too much of this out to the general public.

Here at BSchools, any time we see a business leader with Cohn’s high profile warning a group of federal policymakers that they’d “scare the public” by communicating with them—essentially advising officials to stage some form of a cover-up—we want to know more.

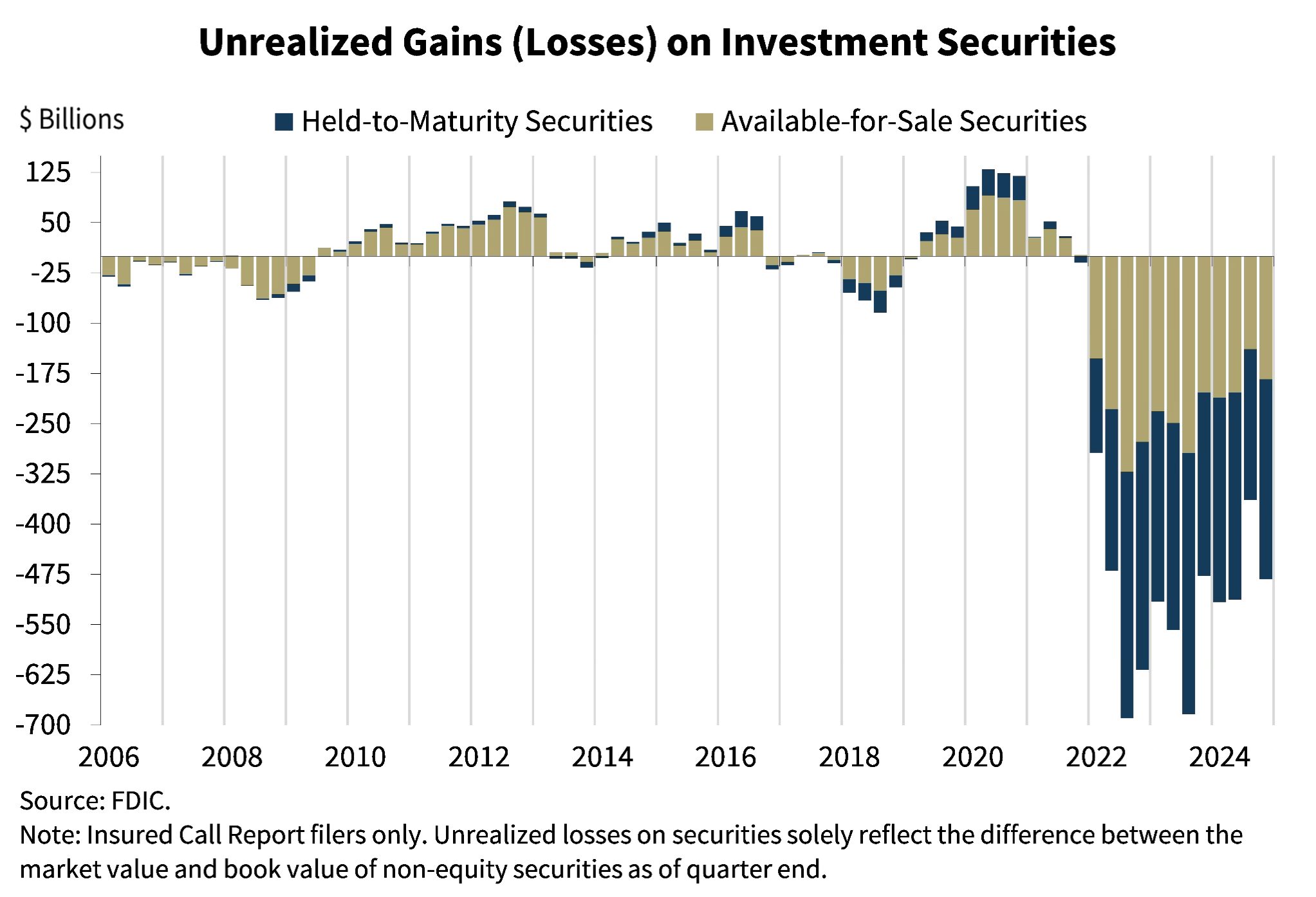

Here’s a clue. The following chart appears in the FDIC Quarterly for 2024 in the banking profile discussing the year’s fourth quarter:

Chart 8 above is the soon-to-be-famous “elephant in the living room” that nobody’s talking about, and that the FDIC would prefer our BSchools readers not know about. Truth be told, it’s probably one of the main reasons that prompted this committee to meet for the first time in several years, as well as why, on the video recording, so many of the participants appear so visibly anxious throughout their nearly four hours of discussions.

What the chart clearly depicts is that unrealized losses on investment securities at the FDIC-insured institutions during the first, second, and fourth quarters of 2024 are unprecedented, and staggering (however, lesser than 2022). In its most recent estimate, the FDIC is now projecting losses in the range of about $482.4 billion.

Stop and think for a moment about the scale of that massive estimate. That aggregate loss value will amount to almost 10 times the losses realized in the worst days of the Great Recession during the third quarter of 2008—a period eventually responsible for the failures of over 500 banks across the United States.